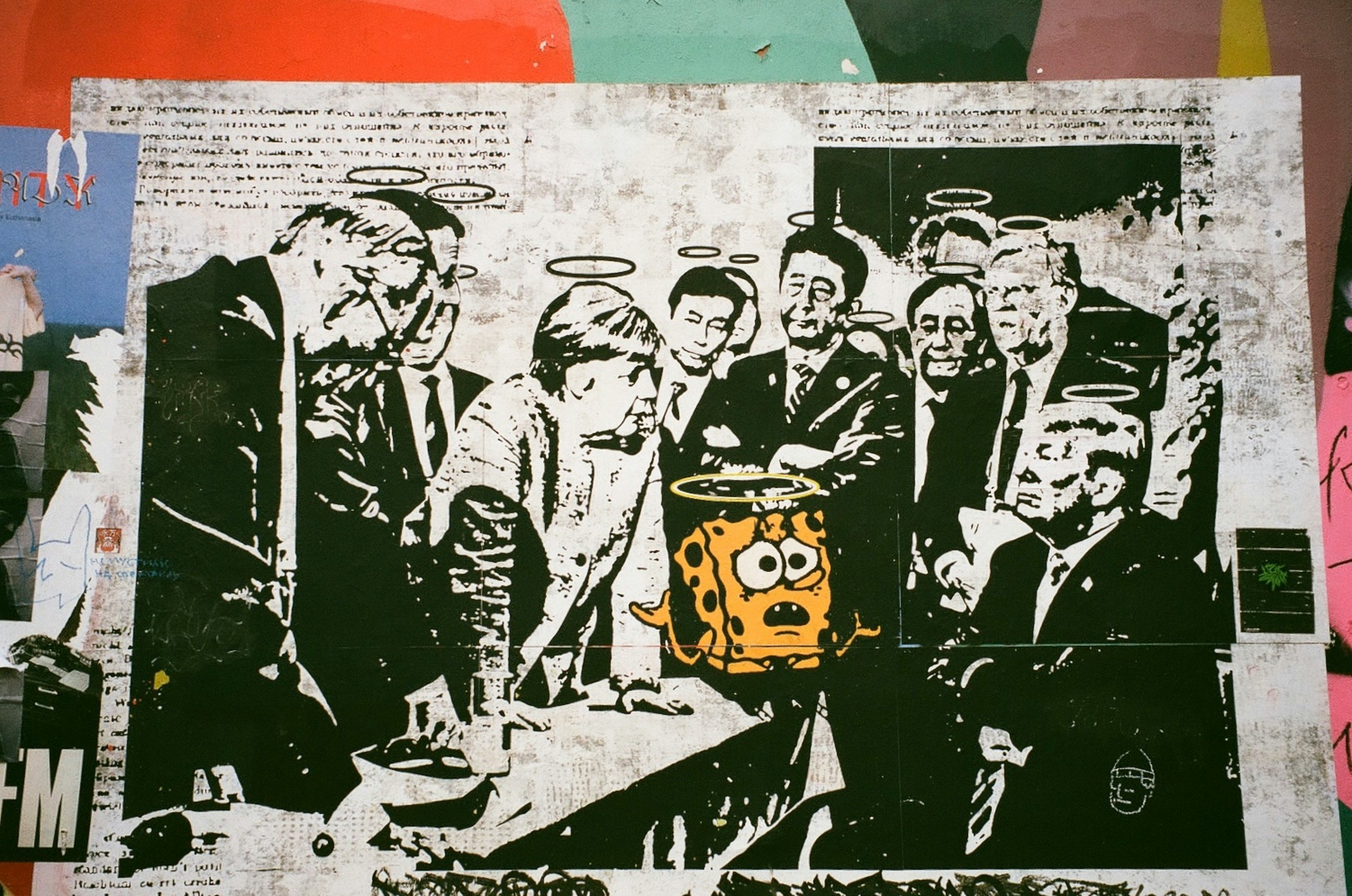

Morality is more akin to fashion than technology… Morality exists like religion exists, neither contains truths… As there is no morality there is no basis for law, and thus all law is one unit of people ruling over others by force… It is in the interests of leaders to disguise their rule as common sense, a Leviathan that cannot be challenged.

— Peter Sjöstedt-Hughes, Neo-Nihilism: The Philosophy of Power

Realising the cosmic indifference of the universe and one’s own lack of power to control or affect events is something every single human being experiences, at least on some level. It is the epitome of the existentialist epiphany, the realisation that time and space are vast and your life is microscopic and insignificant. People deal with it in various ways. They deny it, revel in it, try to keep it at bay with love, with drugs, with wine and song. It’s the oldest question in the world — why are we here? Many people answer this question with a belief. An ideology, in the form of a moral framework; a religion, or a philosophical outlook, or perhaps most often, a political or economic framework for their beliefs.

Many would consider themselves epicures of ideology, picking and choosing what works. Many of us might well be operating under the unacknowledged influence of a larger, more dominant ideology. Perhaps this ideology is publicly defined as not being “ideological” or even “political.” As Slavoj Žižek wrote in 1989:

The very concept of ideology implies a basic, constitutive naivete: the misrecognition of its own presuppositions, of its own effective conditions, a distance, a divergence between so-called social reality and our distorted representation, our false consciousness of it.

In 2020, the government response to the Covid-19 pandemic was explicitly framed as not being “a time for ideology” by the future Prime Minister Rishi Sunak. Yet ideology underpinned everything to do with the outbreak, from response times to social strategy, to the economic measures taken. We are often asked to dismiss ideology from the equation as a dirty, cheap trick, when in fact, sometimes it controls us utterly. The ideological choices made during the pandemic were literally a matter of life and death for every one of the billions of people on this planet.

In this way, the operation of ideology and mind control could be said to be identical propositions, and a tinfoil hat is protection against neither. One is simply the definition of the political actor, the other of the ‘madman’ (another synonym for the ‘other’ — situated as being beneath our consideration). At the site where ideology is enacted or shapes the way things are viewed, it is most likely to be disavowed or framed as ‘natural’ and non-ideological. This is an act of control, but it can be resisted. This is why the so-called post-ideological or post-capitalist analysis of everyone from Francis Fukuyama to Paul Mason is incomplete, because as Žižek wrote just after the fall of the Soviet Union:

If our concept of ideology remains the classic one in which the illusion is located in knowledge, then today’s society must appear post-ideological: the prevailing ideology is that of cynicism; people no longer believe in ideological truth; they do not take ideological propositions seriously. The fundamental level of ideology, however, is not that of an illusion masking the real state of things but that of an (unconscious) fantasy structuring our social reality itself.

Many would argue that ideology is bullshit, especially when we perceive it moving, on the surface. But when it lies beneath; when it constitutes the frame through which we view every political and personal choice we make in life, but we never allow it to be openly acknowledged or challenged, we risk continuing to be someone’s useful idiot. The same is true of morality. Nothing has any intrinsic value except that which we ascribe to it, and this includes our behaviours and our beliefs. As Peter Sjöstedt-Hughes argues:

If everyone shared the same values, then prescriptive morality would be pointless — one would not need to tell people how to behave if they already did so. Prescriptive morality is only necessary when other people act contrary to the way that one would desire them to behave… All prescriptive, or normative, morality is the sought imposition of one person or group’s desire over another. Morality is a power structure.

To put it another way, as Oscar Wilde wrote in An Ideal Husband: “Morality is simply the attitude we adopt towards people whom we personally dislike.” Any deeply-held ideological or moral conviction you find in yourself or others should be scrutinised, examined and pulled apart if you want to know whether it is a belief you simply accepted, one that was drummed into you by your family, school, or profession, or a true value statement you came to be convinced by as the result of sound reasoning and thought.

This need to question your beliefs and the fabric of everything around you should not act as a trigger for inaction or apathy. This questioning is how we actively seek to resist the instinct to pre-judge, to assume knowledge, or to leap to conclusions. The failure to do this questioning is where most people cross from ideological or political belief into prescriptive morality. Before they engage in analysis, morality tells them what to think.

Many people want the story told for them. They are happy to accept whatever ‘conventional morality’ exists in the time and place of their birth as both moral and non-ideological. In this way, as Peter Sjöstedt-Hughes argues, normative morality in any society constitutes a parallel for state religions of the past:

The secular priests of today, predominantly a bourgeoisie, maintain authority and power by prescribing morals here and there. To prescribe is to judge, to put oneself in a higher position of authority, power… If enough heads agree with the ideology, the prescriber / preacher gains further power, eventually influencing standardised law. In relation, the followers of the creed become such followers as the creed offers them more power, even if it entails joining the group, the secular congregation… Only a minority are able to empower themselves without joining a group, an ideology, a ‘false consciousness,’ as even Marx’s Engels put it. Thus normative morality is a tool for power.

We can only conclude that morality is the poor cousin of ideology

For Sjöstedt-Hughes, morality consists in the acceptance of a time-specific set of interlocking prejudices and unexamined beliefs. We can only conclude that morality is the poor cousin of ideology, which at least is something we can attempt to codify, no matter how misguided our efforts may prove. Morality is inconstant, and can be reinterpreted or swept away by events in history very quickly. Yet its ontological insistence is nearly always that it is compulsory, permanent, and timeless, despite all evidence to the contrary. Ideology seeks to convince or explain. Morality wants you to act on your principles, not interrogate them. Moral force, in an argument, is meant not to convince but to control. Often, ideologies cloak themselves in morality to represent themselves as no-ideological.

The most ‘moral’ ideology is of course the ‘correct’ one for most people. For the vast majority, there is the status quo, and the promised land. One never changes, the other never arrives. So-called moral ideologies are those seen to be positive, as Julie Reshe writes:

Everything justifies its existence with a positive purpose. Politics as such and any social projects are, by definition, positively oriented; they are designed to improve the existence of the individual and society. Leftists, neoliberals, and conservatives compete in who will improve society and the world better. Something that does not offer an improvement will not even be qualified as a political or social project. This is where leftists, neoliberals, and conservatives coincide; even fascism coincides with them because it implies its own idea of a better future.

Utopia is the territory of desire, just as morality is the manifestation of shame-at-desire, the repressed sexual urge. That is why utopian politics are ultimately a pressure release valve rather than a revolutionary project, as the Situationists appreciated. This is one reason the rhetoric of mainstream leftist parties is only, and can only ever be revolution-lite. Pretty words barely conceal the unquestioned acceptance of the political mainstream’s free market logic, which is that of unfettered capital. Once something is accepted as post-ideological, its effectiveness is presented to us as not possible to question, even if its effects completely contradict its intent. In other words, it has gained the force of a moral argument.

Morality makes a thin shroud, so the mainstream left’s unwillingness to think beyond the ballot box is as much of a betrayal of the working classes as the right’s flagrant attempts to paint austerity as a logical restorative for overspending. These are both problems neither side wants to solve, and the moral arguments around them are obscene in that context. These problems of morality are ancient. But to consider them settled, or rationalised, or solved by enlightenment ideals or technological progress is absurd. Hidden and overt moralities are everywhere, as are implicit and explicit ideologies.

Awash in a sewer-tide of media, with thinkpieces and hot takes to consume, all informing and influencing the way we view our work, our lives, our creativity and our friendships, how do we navigate? Sjösted-Hughes offers a solution that is simple to express, but challenging to accept and follow: “We must distinguish descriptive from prescriptive ethics; and human characteristics from values and vices.”

Support my work:

Explore my writing: linktr.ee/bramegieben

Read my book: linktr.ee/thedarkesttimeline

Follow @strangeexiles for updates on Instagram and Twitter